The Legacy of Anne Frank: 65 Years of Wonderment and Inspiration

In August 1944, diarist Anne Frank and her seven companions-in-hiding were arrested by the Nazi Gestapo in Amsterdam. Shortly thereafter, most of the group was transferred to the Auschwitz death camp in Poland. With the Soviet liberation of Poland in progress in the fall of 1944, Anne and her sister, Margot, were selected for labor duty because of their youth and sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. Both sisters contracted typhus and died in March 1945. Their deaths occurred only weeks before British troops liberated Bergen-Belsen in April.

For the last 65 years, Anne Frank and The Diary of a Young Girl, her disquieting chronicle of seclusion and human spiritedness published in 1947, have never been absent from the world's consciousness. Whether it is because Anne Frank represents innocence and morality in a time of vicious brutality or because the pages she composed capture the essence of human forbearance, there exists an enduring desire to remember her and a constant endeavor to comprehend the magnitude of her suffering.

To that end, Anne's seminal work was adapted into a play in 1955, with the movie version following in 1959. The book has been translated into dozens of languages, and new scholarly editions of the diary, which critique the craft of Anne's writing and analyze sections omitted from the original publication, are published with some regularity.

Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife by Francine Prose is the most recent contribution to the study of Anne Frank. In her book, Prose posits that "Anne crafted a memoir that has become one of the most compelling documents of modern history.... [With] ever-increasing maturity, she described life in vivid, unforgettable detail, explored apparently irreconcilable views of human nature—people are good at heart but capable of unimaginable evil—and grappled with the unfolding events of World War II, until the hidden attic was raided....

And Prose addresses what few of the diary's millions of readers may know: this book is a "deliberate" work of art. During her last months in hiding, Anne Frank furiously revised and edited her work, crafting a piece of literature that she had hoped would be read by the public after the war.

Read it has been. Few books have been as influential for as long, and Prose thoroughly investigates the diary's unique afterlife: the obstacles and criticism Otto Frank faced in publishing his daughter's words; the controversy surrounding the diary's Broadway and film adaptations; and the claims of conspiracy theorists who have cried fraud, along with the scientific analysis that proved them wrong. Finally, Prose, a teacher herself, considers the rewards and challenges of sharing one of the world's most read, and most banned, books with students.

How has the life and death of one girl become emblematic of the lives and deaths of so many, and why do her words continue to inspire? Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife tells the extraordinary story of the book that became a force in the world. Along the way, Francine Prose definitively establishes that Anne Frank was not an accidental author or a casual teenaged chronicler, but a writer of prodigious talent and ambition." (Courtesy of Brookline Booksmith)

Francine Prose appeared recently on C-SPAN's BookTV to discuss her book. You can watch her presentation by clicking on this link: Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife

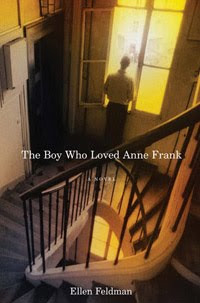

While Anne Frank's influence and significance are often evaluated within the genre of nonfiction, her story— as well as the story of those who hid with her— inspired Ellen Feldman to write the speculative The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank (2005). Selected as a New York Times Book Review “Editors’ choice,” Feldman's novel is inventive and uniquely provocative. As the book review columnist for the former publication MotherTown, I reviewed The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank. Here is that review:

Peter van Pels was born on November 8, 1926. He was a German Jewish refugee who, along with his parents Hermann and Auguste, went into hiding with Anne Frank during the Nazi Occupation of the Netherlands. The van Pels joined Anne’s parents, Otto and Edith Frank; her sister, Margot; and Fritz Pfeffer in the “Secret Annexe” in July 1942.

In The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank—one of the world’s most widely read books that recounts what daily life was like during the two years the group spent in hiding—Anne relates that she and Peter, to whom she gave the pseudonym Peter van Daan, developed a deep friendship and a romantic attraction for each other. Anne wrote: “I . . . never had someone I could confide in. . . . I’m so lonely and now I’ve found comfort!” And, it was Peter who gave Anne her first kiss.

On August 4, 1944, the Grüne Polizei, (a division of the Security Service) stormed the group’s hiding place and arrested everyone. The men and women were separated—never to see each other again—and transported to concentration camps. Hermann van Pels was gassed at Auschwitz in October 1944. Auguste van Pels died sometime in April 1945, either during the forced march to a military base in Czechoslovakia or shortly after arriving. Fritz Pfeffer died of starvation at Neuengamme in December 1944. Edith Frank died of malnutrition at Auschwitz in January 1945—twenty-one days before the Red Army liberated the camp. Margot died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen in March 1945. Anne, also at Bergen-Belsen, died of the same disease within days of Margot and within weeks of the camp’s liberation on April 15 by British troops. It is not known whether Peter van Pels died during a forced march out of Auschwitz or perished at Mauthausen sometime between April and May 1945. Otto Frank was the sole survivor.

In 1994, author Ellen Feldman (Lucy, 2003) visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. A guide remarked during the tour that there are records that document the fate of all of the inhabitants of the Secret Annexe except for one: Peter van Pels. Feldman’s “imagination was captured” by this mythical possibility: “If this young man did not die with the others, I speculated, what might he have go on to?”

Feldman discovered during the research for this novel that the tour guide was either “misinformed or romantically inclined” and that Peter indeed died; but by the time Feldman made this finding, “Peter van Pels had been living in [her] mind for several years.”

So, Feldman stayed with the premise that Peter survived. The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank is Feldman's marvelous, speculative tale of the life that Peter van Pels may have created for himself after World War II. It is a terrific novel, one that captures our imaginations and forces us to question how much of our memories and our pasts should we allow to define and influence our present. Can we even escape our pasts? And what do they become if we deliberately alter our memories of them? Did they still happen, or have we transformed them from being a part of our reality to being a part of our imagination?

The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank begins in 1952. Peter is the narrator. He has been in the United States for six years, and no one knows anything about his past. He disavows being Jewish. He is 26-years-old; happily married; a father; an American citizen. He is edgy, sarcastic, circumspect, and apprehensive.

We first meet him during a session at his psychiatrist’s office. Peter has lost his voice. Dr. Gabor plies Peter with questions in order to ascertain the cause of this odd state of speechlessness. Peter whispers curt, evasive responses, deflecting Dr. Gabor’s prying for fear that his answers will reveal too much of the Peter van Pels that he once was.

In his mind, though, Peter replays the history and events with which he has had to reckon since leaving Amsterdam and arriving in America. Silently, in his monologue, he tells us of the “spitefulness” of memory: “[M]y existence before [“my current life”] is a mystery. Even when I’m trying to remember it I have difficulty. . . . I know certain facts about my life. I can even put them together in sequence, because that must be the way they occurred. But I have no recollection of when things happened, or where they happened, or even if they happened to me or someone else. I was born six years ago in a customs shed on the Hudson River. I was conceived a year before that on a lightening-charged night in a dung-smelling barn somewhere in Germany. Any previous existence is a rumor I overheard. Instead of memory, I have instincts; in place of a past, I have this inexplicable, ill-gotten, entirely remarkable present.”

Peter also remarks on the mild, “palliative” language used to “keep the unthinkable at bay,” “all-purpose” words spoken by people who know nothing about torment to describe the horrors of a world beyond imagination. He confides that “Home” is one of his favorite English words..

We soon discover the reason for Peter’s lost voice. It has to do with the publication of Anne’s diary and its subsequent adaptations into a play and a movie—both of which misrepresent actual events. The deprivation and brute misery that Peter endured has become the stuff of casual conversation and entertainment. The popularity of the attic-dwellers’ plight is unavoidable—Peter’s own wife is fascinated by the story—and Peter is beset by reminders of his past and tortured by the distortion of facts.

Having his history publicized is a threat that provokes the near-breakdown of Peter’s fabricated world and identity. We become engrossed in Peter’s telling of his desperation; his attempts to keep his two worlds from colliding; his rage at having to confront Anne’s fame, a celebrity status that he finds perverse; his fractured memories of what happened in the attic versus the “pack of lies” that the play and movie maintain.

Should he reveal the truth? he wonders. Would his “cosmic sin” be forgiven? How long can he hide behind the pseudonym Anne gave him? Should he tell his wife? If he does, what could he expect her response to be?: “Would she tell me to stop joking, because this is not a laughing matter? Would she believe me? And if she did, then what? Would she take me to her bosom? Would she shoulder my suffering? Would she slip the silvery key of her love, brightly polished like all the silver in the house, into the lock of my past and twist it?”

Accompanying Peter as he meanders through the muck and anguish of his present and tries not to let the recollections of those harrowing days and nights in hiding consume him is a remarkable journey upon which we gladly embark. Feldman has given us a tremendous character in Peter. He is marked by trauma, but he is not stymied by it. He has seen humanity’s wickedness, yet he believes in, and treasures, love. Feldman imbues Peter van Pels with an authenticity seldom encountered in contemporary historical fiction, and the narrative she has created captivates. The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank is an outstanding success. It is an unforgettable story.

Comments